SM0486

b. As shaft "A" and the contactor are pressed against a rotating

object, the collar "B" is forced up shaft "A" by the centrifugal force of weights

"W" pulling outward, acting through pivots "C" and "D" and "E".

Note that the

pointer is attached to collar "B". Adjacent to this pointer is an RPM scale. The

faster the rotating object turns--the greater the force of weights "W" pulling

outward--the farther collar "B" will move carrying the pointer upscale.

c. The advantages of the mechanical tachometer are that it is

economical and simple to operate.

The major disadvantage of the mechanical

tachometer is its loading effect on the rotating object. For example, suppose the

maximum speed of a small electric motor is to be checked. Because of the loading

effect (slowing down) caused by the pressure of the mechanical tachometer, a true

maximum speed of rotation will not be indicated.

The other rotary measurement

divides in this section do not have a loading effect on the rotating object.

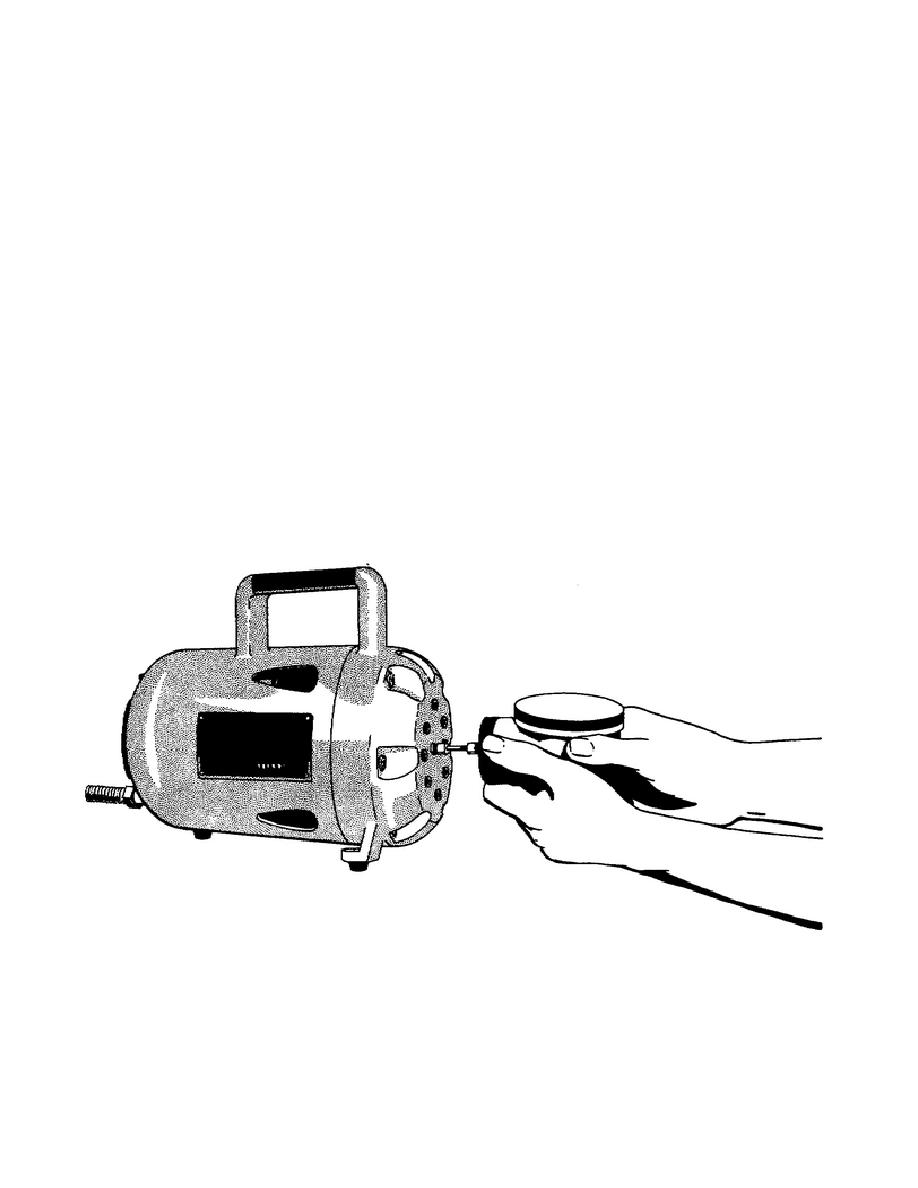

d. Mechanical tachometers can be calibrated by means of a tachometer

tester such as the Sweeney Model 1000 shown in Figure 4. The Sweeney Model 1000

tachometer tester is a synchronous motor with seven gear driven output shafts of

known rotational speeds. The rotating speed of the synchronous motor is as stable

as the frequency of the alternating voltage applied to it. Since the frequency of

the power supplied by major power companies is regulated to within 0.1 cps, the

rotational speed of the mechanical outputs of the Model 1000 is extremely accurate

and suitable as a standard for calibrating mechanical tachometers.

Figure 4.

Sweeney Model 1000 Tachometer Tester

82

Previous Page

Previous Page