Although his thermometer has been improved upon, it is still not used for accurate

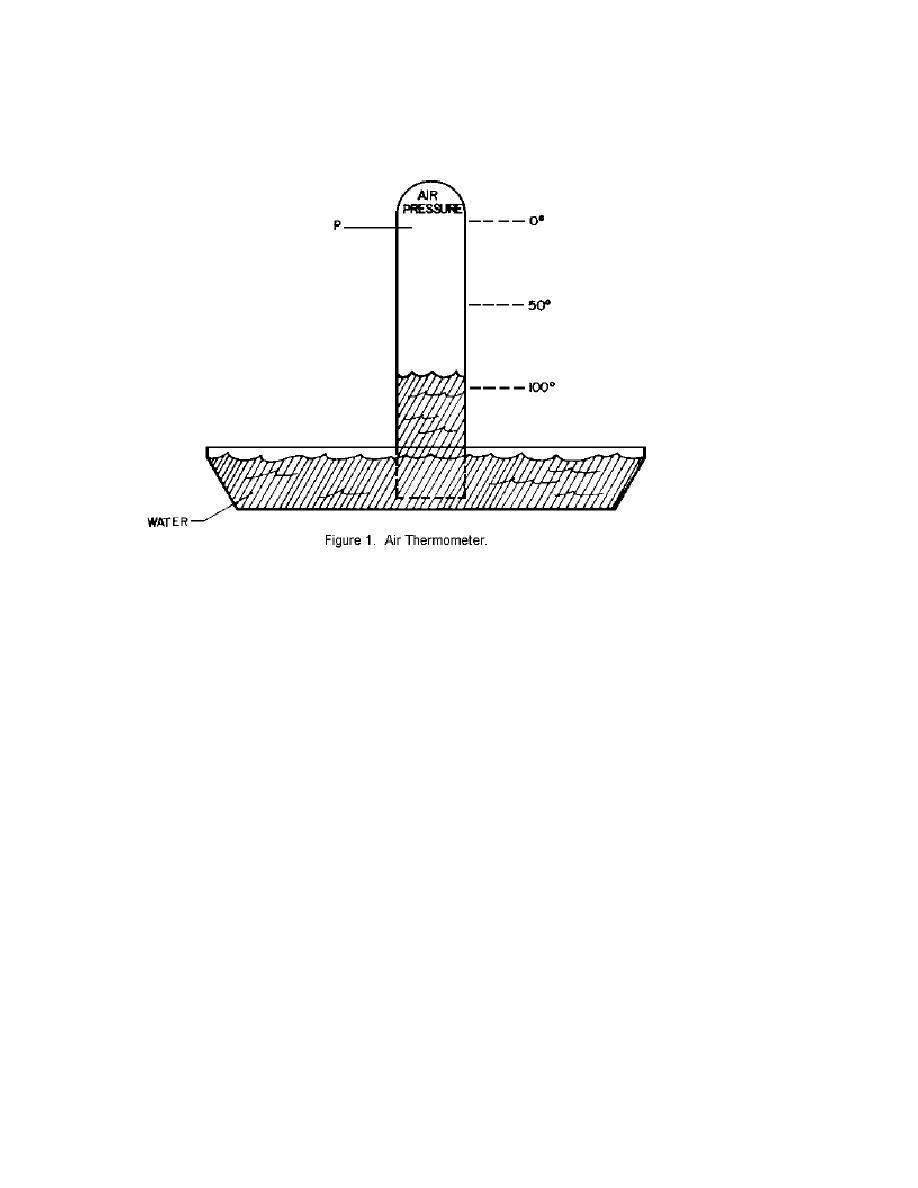

measurements. Basically, the air thermometer is a glass tube with an opening at one end

and a bulb at the other end. The open end is submerged in a dish of water.

The air trapped in the bulb expands as the ambient (surrounding) temperature increases,

thus the increased air pressure (P) forces some water out of the tube. The water level of

the tube is related to a scale giving an arbitrary indication of temperature. Detrimental to

the accuracy of the air thermometer are changes in atmospheric pressure which vary the

water level. Also detrimental is the fact that water evaporates.

The useful range of this instrument is limited, as it operates between the freezing and

boiling points of water.

It is apparent from the description of the air thermometer, that a more accurate and

dependable means of determining temperature was needed.

3. CLOSED-GLASS LIQUID THERMOMETERS.

Leopoldo, Cardinal de Medici made the first closed-glass liquid thermometers, around

1654. These thermometers, widely used in France and England, were graduated into 50,

100, or 300 degrees. They were roughly standardized by the heat of the sun and the cold

of ice water, and filled with distilled colored wine. The advantage of a liquid like wine

was that its expansion was independent of air pressure. Mercury and water thermometers

were also tried by the Florentines but abandoned because there expansion was too small.

Later this problem was overcome by making thermometers with finer bores, thereby

increasing their sensitivity, and by the middle of the 18th century mercury thermometers

had superseded others because of their near uniform expansion, low freezing point and

high boiling point. The mercury thermometer consists of a narrow glass tube (called a

capillary) with a bulb blown on one end to act as a reservoir for mercury. The other end

of the tube is sealed after all the air is evacuated (refer to figure 2).

Previous Page

Previous Page