(b) Calling.

Sometimes when the observer has his hands full

making the observation, he is unable to record the data. At such times, he

calls out his readings to an assistant, who records the information.

The

caller's voice should be clear and sharp, and the assistant should have good

hearing.

In more complex experiments, two observers may call readings to

one recorder, especially when simultaneous readings are needed. When a more

complete record is required, a tape recording can be made and the data

transcribed, or rechecked later.

(c) Writing. Anyone who records data of any importance should be

able to write clearly and sharply.

The characters should be legible,

uniform, and in proper alinement. This is no place for a person who makes

chicken tracks for numbers.

(d) Forms.

Many laboratory procedures have the aspect of

repetition; hence, the use of appropriate forms is a labor-saving device as

well as an error-preventing technique. Forms should be clearly titled with

spaces for all pertinent information as well as the measurement readings.

Columns should be headed with titles.

Sometimes the processes or the

mathematics involved are indicated by the layout of the form. There should

be general purpose forms as well as those specific to a particular

calibration. When a form is not available, it is better to improvise one

rather than to use a blank sheet of paper.

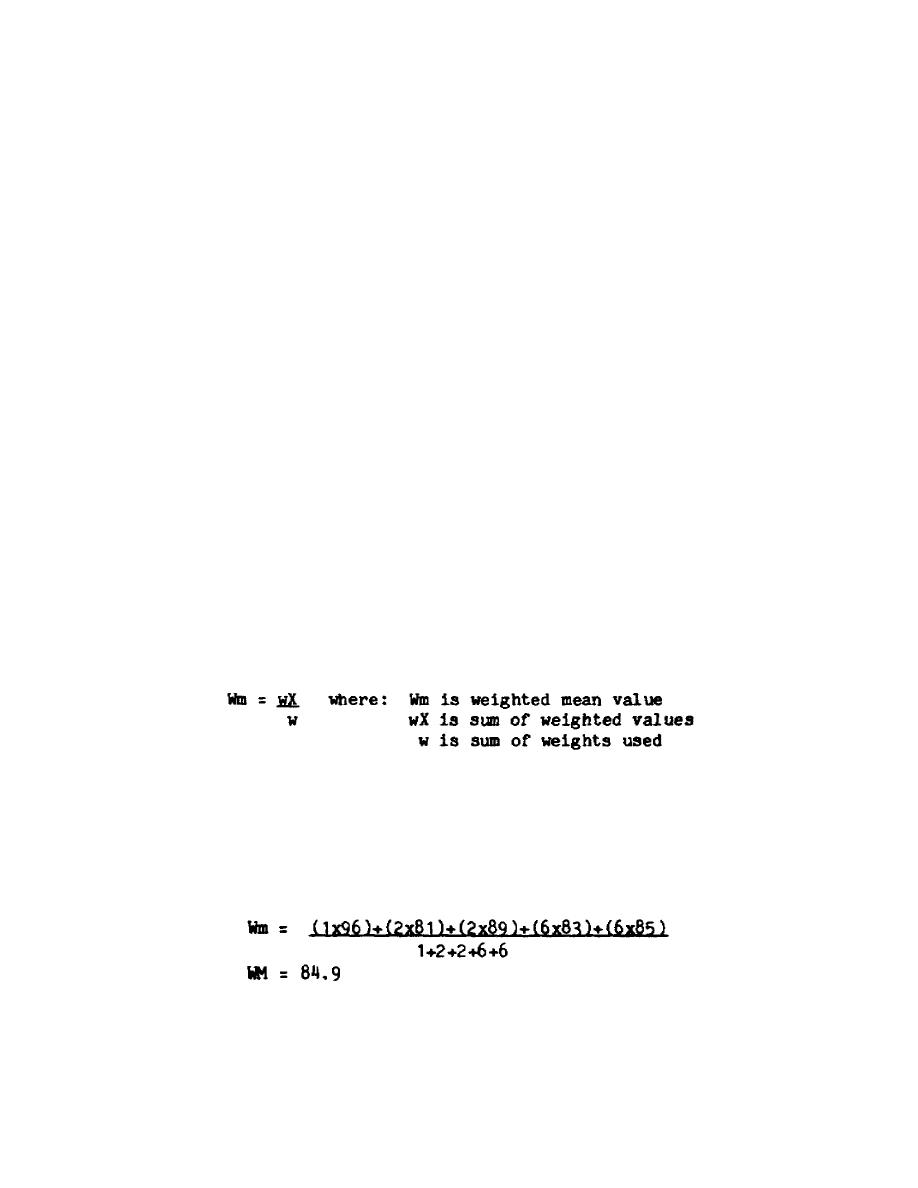

(4) Weighting data.

(a) At times, you may encounter a set of data which is made up of

values all of which are not equally trustworthy. It would be incorrect to

give them equal weight when averaging, yet you may not feel like

disregarding the doubtful readings. You can improve the probability of the

validity of the average by a process of weighting. The formula is:

(b) For example, let us say that the following readings were made:

81, 83, 85, 89, and 96. Due to the conditions of measurement, it is felt

that the 83 and 85 measurements are three times as likely to be accurate at

the 81 and 89, which are twice as likely to be accurate as the 96. Thus we

want to weight 83 and 85 at 6, weight 81 and 89 at 2, and weight 96 at 1.

Set it up as follows:

(c) This process allows the low-probability values to influence

the average but not as much as the high-probability values.

The

statistician can assign any weights he feels are appropriate.

151

Previous Page

Previous Page